"How To Draw An Indian In Three Steps": Indian Comics As Self-Determination and Decolonization, Part 1

In the first installment of this series, I address a brief history of Native comics and see how the evolution works for self-determination and decolonization in contemporary Native comics.

The history of Indians in comics/graphic novels is a long and winding road. Stretching across a century, Native artists/authors are only now gaining traction with their works. This series seeks to explore three different, interrelated areas that have helped to shape the arc of Native comics/graphic novels. Looking at Language, then Image, this first article looks at the context of the Native image/icon in the glamorized American pop culture, and how Native/Indigenous artists, authors, and activists view the relevance of this conversation. Not being marginalized by one established image/icon of the Native superhero, this article seeks to provide the argument for tribal self-determination and sovereignty on the foundations of a decolonial qualification. This article does not emphasize an artist, style, or narrative. The work provided is to learn more about the discipline and contextualize it.

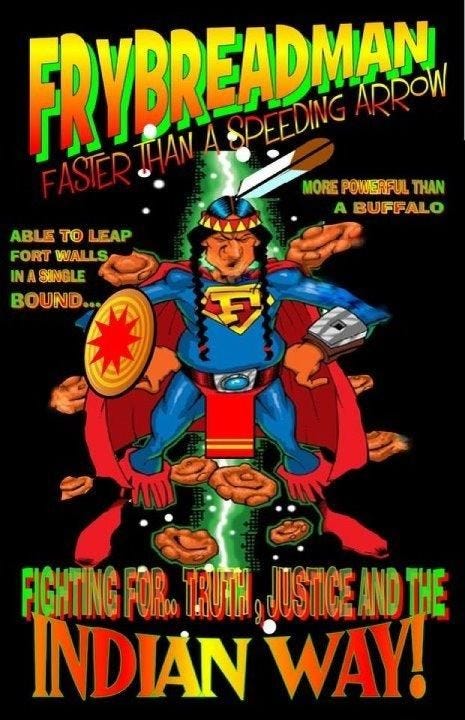

“Frybread Man,” a Superman send-up, is ‘Faster than a speeding arrow…more powerful than a mighty buffalo…able to leap tall pueblos in a single bound….’ In his comic strip, Marty Two Bulls Sr. (Oglala Lakota) takes on racial stereotypes, the consequences of environmental destruction, and economic struggle” (qtd in PBS News, April 2009).

Historical Context And Evolution

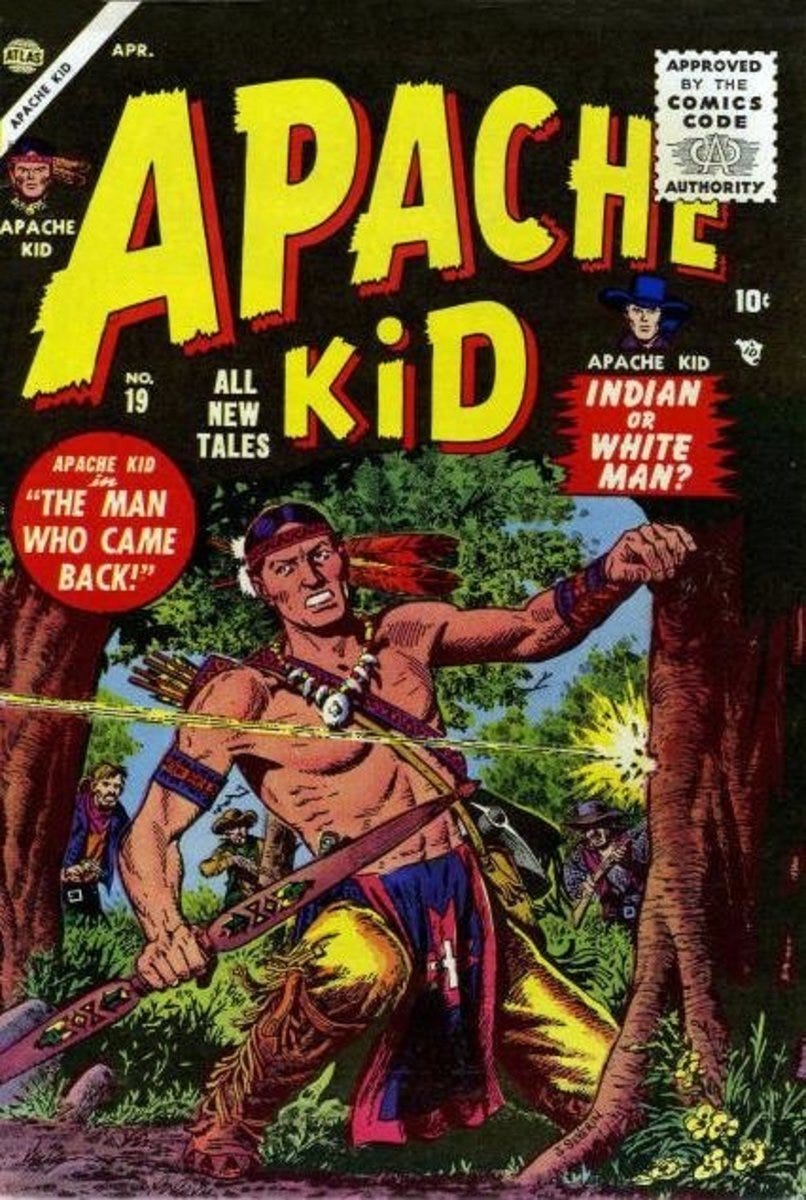

The progression of Native characters, advancement of Indian Talk, and the localization of these characters in more fantastical and realistic situations aligned with the currency of the comic/graphic novel industry brings relevance to Native identity. Remaining true to the medium, Native comics do not work along the fallacy lines of authenticity, or detailed tribal culture, customs, knowledge, traditions, or expressions. Contemporary Native comic/graphic novels arrive at a point to forcibly contest stereotypes and racist images of Indianness in comic books, seen as far back as the 1890s.

“Some of the earliest depictions of Native Americans in American fiction were in the dime novels that were popular in the late 19th and early 20th century. To the frontiersmen marching ever westward, the indigenous peoples of the United States were little more than savage heathens, an obstacle to be overcome on their path to manifest destiny. And it was in these dime novels that the groundwork was laid for what would become the prevailing image of Native Americans for decades to come” (Emmett Furey, CBR, January 2007).

The progression of these dime novels extended into the start of film. The racialized stereotypes of the Indian image/icon in these early works remained and were concertized further as the early 20th century began.

“With the advent of the motion picture in the early 20th century, the medium that would one day supplant literature as the primary mode of American escapism, adopted a similarly skewed view of Native Americans. The Western genre was as popular in the action-adventure serials as it was in dime novels, and the serialized storytelling from which the weekly installments got their name, as well as the cliffhanger plot device that the serial pioneered, were just a few of the ways that early film influenced the burgeoning medium of comics when the comic book first penetrated the public consciousness in the 1930s” (Emmett Furey, CBR, January 2007).

The advancement of Native comics began to flourish further after the 1930s. It is here where we see the evolution of numerous Native American superheroes that has continued to extend to the current comic/graphic novel genre.

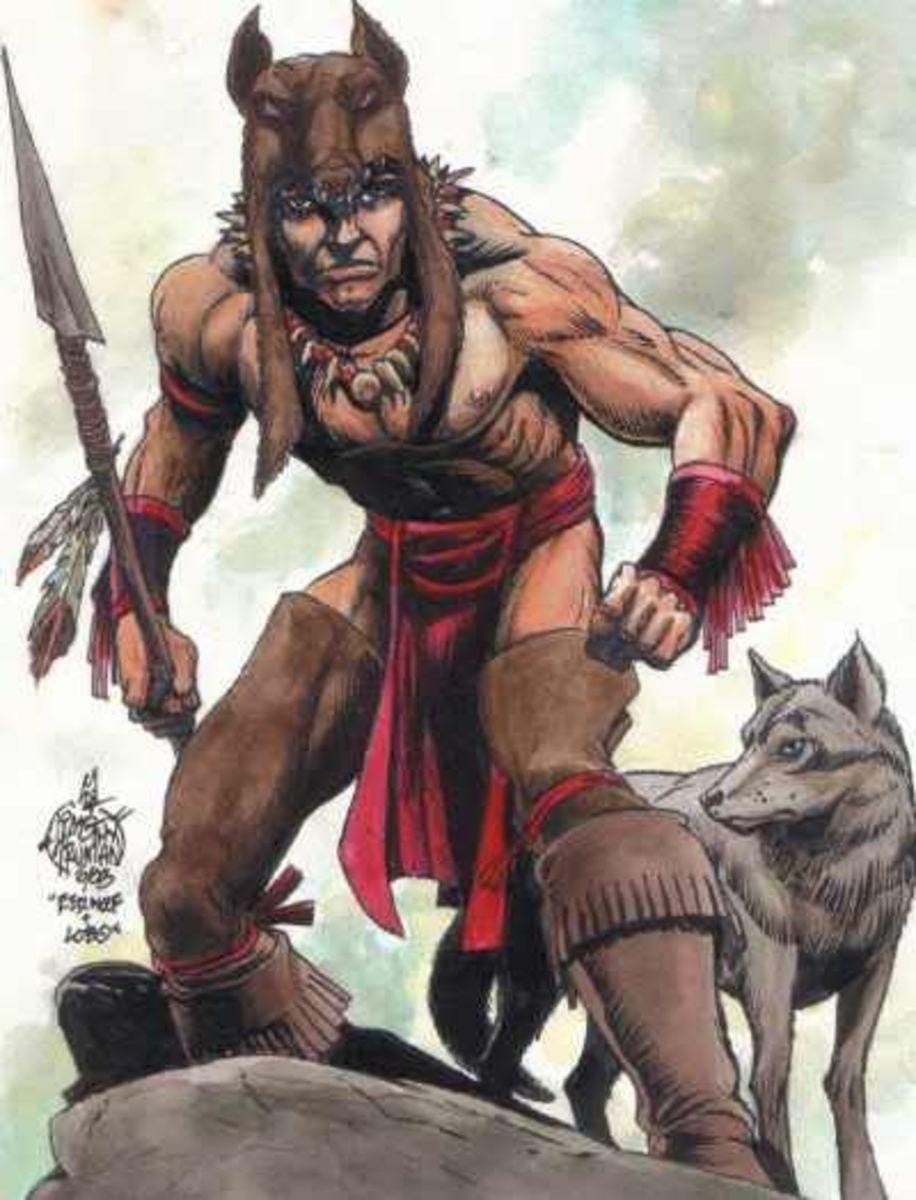

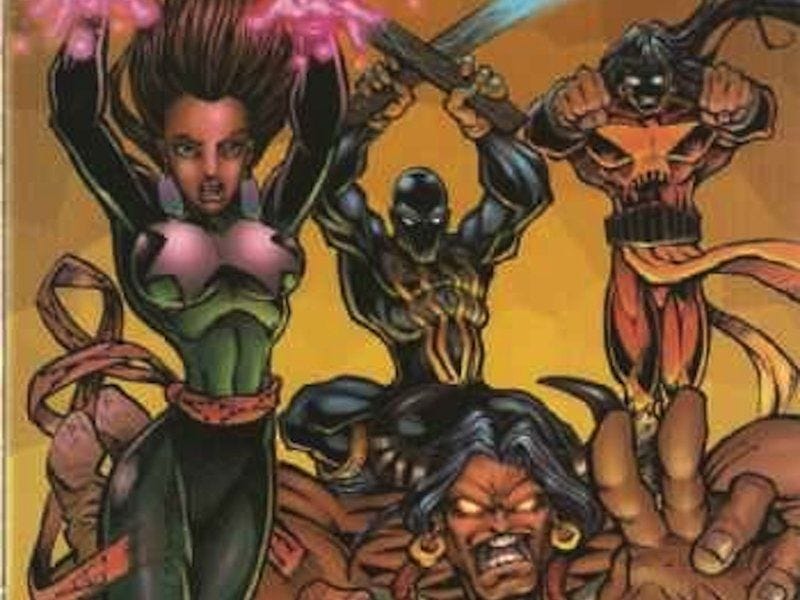

Warpath (James Proudstar): An Apache mutant and member of the X-Men, Warpath possesses superhuman strength and agility. He is known for his role in various X-Men storylines and has a rich backstory connected to his heritage.

Moonstar (Danielle Moonstar): A Cheyenne mutant with the ability to create illusions based on people's fears, Moonstar is a prominent member of the New Mutants and has been featured in various X-Men-related comics.

Turok: Originally a character from the 1950s, Turok is a Native American warrior who battles dinosaurs in a prehistoric setting. He has appeared in various comic series and video games, making him a well-known figure in pop culture.

Puma: A character from Marvel Comics, Puma is a member of an unnamed Native American tribe and has often crossed paths with Spider-Man. He possesses enhanced strength and agility.

Dawnstar: A member of the Legion of Super-Heroes, Dawnstar is of Native American descent and has the ability to track anyone across the galaxy. She is known for her strong sense of justice and her connection to her heritage.

Chief Man-of-Bats: A character from DC Comics, he is a member of the Batmen of All Nations and represents Native American culture through his superhero persona. (Wikipedia, February 2013).

Analysis For Representation

An interesting point noted by Raymond Wilson in his article, “When superheroes go native: Comic books and the images of American Indians since 1940,” positions Indian Blindness.

“From the various comic books studied and the oral histories conducted with comic book writers, the theme of Indian Blindness emerged in that American Indians are not a "vanished race" in contemporary society, but more often an invisible one” (Wilson, Raymond Nathan, “When superheroes go native: Comic books and the images of American Indians since 1940,” Open Research Oklahoma, December 2007).

This comes out of the history of racist portrayals of the Indian image/icon in the early inclusion of the image/icon in American pop culture. Indian Blindness is a form of erasure; a silencing of the Native voice and expressive culture. The reference of the Indian image/icon in the American pop culture psychology codified a colonial doctrine, ownership, and privilege of the Indian icon/image by the large non-Native community. The ramifications of this artistic ownership and dominance are witnessed in the mascot controversies and throughout each of the expressive disciplines. Misappropriating Indianness was seen as a lucrative market in high demand. This economic oppression fueled the gross inclusion of the stereotyped Indian image/icon and continues to be an exploitative market today, in 2025.

Native artists and authors working in the comic/graphic novel genre took hold of these overwhelming inaccuracies not to re-create a hyper-accurate representation of Indianness. Rather, the summary of the works is to display an inner voice of the Indian while expressing an external image of a fantastical Indian image/icon with ties to overarching tribal culture, customs, knowledge, traditions, and expression borrowing from other popular comic superhero themes and scripting these through an active Native lens.

The space, environment, and location of tribal culture, customs, knowledge, traditions, and expression, in Native authored comics/graphic novels contest the historic reference of Indianness with a contemporary application. This frames Native/Indigenous decolonization over resistance. Where decolonization provides the liberty of Native lexicon(s) to exist with progression along the rights of self-determination and sovereignty. Resistance limits the progression of Native identity politics. Resistance must have a base to work against. This socio-political, economic, environmental, and socio-religious tie to colonial ideology places control of resistance strategies with the colonial doctrine being resisted. The limits of resistance are drawn and maintained by the external oppressive power. Resistance exists as a border culture; decolonization exists as a border-crossing culture.

Another interesting article from C. Richard King, “Alter/native Heroes: Native Americans, Comic Books, and the Struggle for Self-Definition” (December 2008), points to the positive development of Indianness by Native graphic artists and authors through history as agency to reclaim and correct Indian representation.

“[I]t details the prominence of anti-Indianism in comic books, particularly as means through which Euro-American authors and audiences have made claims on and through Indianness…it unpacks the use of comic books to challenge and question dominant misappropriations and misunderstandings…it examines the recent emergence of indigenous comics intent to use the medium to reclaim Indianness. In conclusion, it proposes that the alternative uses of comic books should be read as an excellent example of a larger movement for visual sovereignty in native North America” (King, “Alter/native Heroes: Native Americans, Comic Books, and the Struggle for Self-Definition,” Sage Publication, December 2008).

The points here contextualize how Indianness has moved through history from colonial possession to a decolonial position. Underscored in King’s argument is the right of self-determination and expressive sovereignty. The challenge to “misappropriation of Indianness in North America” has been an ongoing issue, most prominent to the large non-Native community in the mascot controversy. The present and existing dialectic in racist American Indian mascots is inverted in graphic comics created by Native artists.

King counters the argument of Wilson, who concludes that comics are a useful tool for Native identity, but do little in the way of moving the needle toward active and contemporary representation. Wilson notes the ongoing stereotypes that remain present in Native comics (Wilson, 2007). King, in contrast, notes the value and importance Native comics provide for tribal identity, contemporary Indianness, and juxtapose against historic stereotypes and racism, which was prominent in the early history of Native American comics, c. 1940s.

The juxtaposition of these two authors brings to light the contemporary counterpoints used by insider-outsider identity politics. It is through the Native lens that Indianness has ambivalent opportunities to first survive from historic institutionalized racism to, second, exist as a self-determination and sovereign image/icon in comics/graphic novels.

Updating The Image/Icon

The “Comic Art Indigene” hosted by the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. (2009) works to advance the representation of Native Peoples in comics past historic stereotypes.

“…American Indians and comic art. In times past, both were considered ‘primitive and malignant’ forces on American society, but both are actually ‘complex and adaptive.’ ‘It is only natural,’ the introduction says, ‘that this marginal art appeals to oft-marginalized indigenous people….’” (qtd in PBS News, April 2009).

The Smithsonian exhibit on Native comics was curated as a vehicle to express the necessity of this medium in supporting a positive quality of Native identity.

“Until recently, American Indians appeared only as stereotypes in comic books, their real narratives…[were] obscured by generic images of teepees and headdresses. This exhibit shifts the focus of the comic panel to expose the true culture that the old comics left out” (qtd in PBS News, April 2009).

The history of Native comics/graphic novels is finally coming into its own. The genre is being widely fueled by multiple young and older Native artists and authors. The community of Native artists and authors works, as an unspoken fundamental, to promote a positive and conscious representation of the Indian image/icon. Not to speak for any one tribe or Indian entity, Native comic /graphic artists are more interested in embracing the fantastical genre to narrate the discipline with an active Native voice.

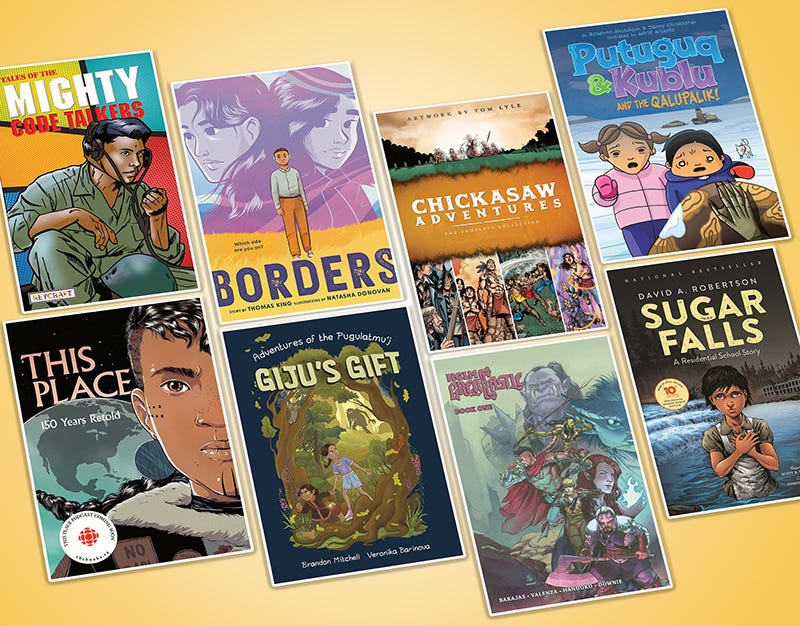

Some Locations For Comics/Graphic Novels By Native Artists/Authors

A valuable list of books and series by Native graphic artists can be found at Colorin Colorado. The page “Graphic Novels and Comics: American Indian Heritage” contains multiple suggestions and additional links.

“Alter/native Heroes: Native Americans, Comic Books, and the Struggle for Self-Definition” is available through Sage Publications. The bibliography of this work is published with links to additional resources.

“Nine Native American Graphic Novels, Stellar Panels,” Bridget Alverson, November 2021, is a useful site with links to numerous graphic novels by Alaskan Natives/Inuit/Aleut graphic artists. The list includes graphic novels for youth through more focused tribal commentaries.

Alan Lechusza Aquallo